I know a film is special to me when I emerge from the dark theater and onto the streets, my eyes adjusting their aperture to the change in brightness, and I just have to walk around for a little while. Something on that screen struck me, and like the burst of a gong, I’m waiting for the vibrations to dissipate. I felt that walking out of the Walter Reade Theater during the 61st New York Film Festival after seeing Annie Baker’s Janet Planet. It didn’t have the scale of films like Poor Things or The Zone of Interest, which also screened during the festival but that’s what’s most miraculous about Baker’s film directorial debut.

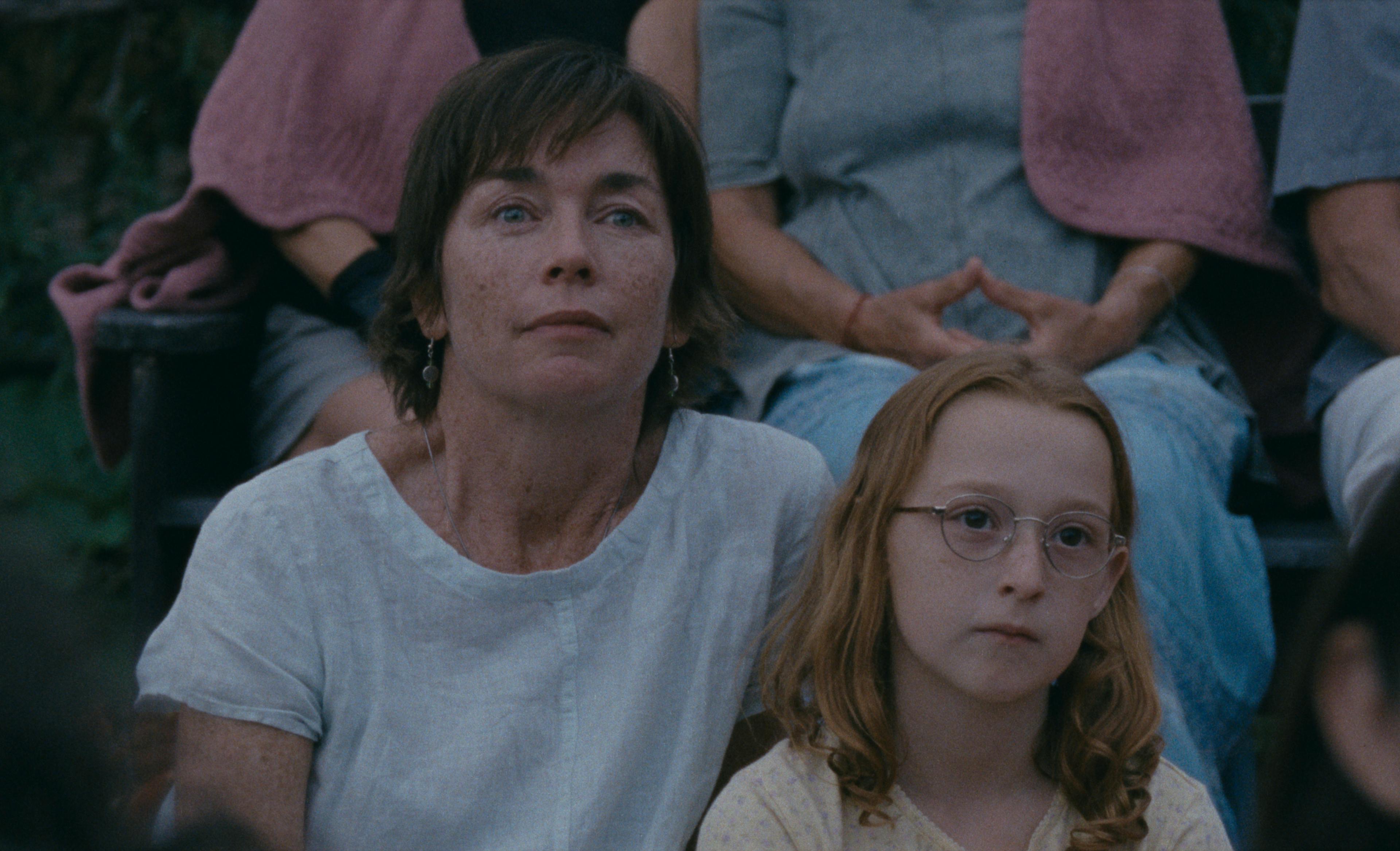

Janet Planet is the unassuming story of Janet, a single mother played by Julianne Nicholson, and her cautious but precocious daughter Lacy, played by newcomer Zoe Ziegler. The two share a close orbit as they inch their way through a summer in rural Massachusetts after Lacy’s unsuccessful stint as a summer camper. Lacy’s inward nature reveals a world rich in imagination that almost feels too precious to share with the outside world. Outside of that personal space, she finds solace mostly in her mother, who runs a small acupuncture business out of their home. There isn’t much else around. Their serene harmony is disturbed in the presence of the new people Janet brings into their lives.

The new entrants to Janet & Lacy’s world embody their own section of the narrative. Each section acts like a chemistry experiment; the two constants reacting in different ways to the variable. The characters, denoted by their own title card, agitate and excite the two in different ways. Wanye, Regina, and Avi (played respectively by Will Patton, Sophie Okonedo, and Elias Koteas) are all partners to Janet, who seeks them out in her ennui for connection in the lonely sticks of New England.

At one point, Janet and Regina share a drug-induced trip, Janet presents a psychological knot she struggles to untangle. She describes a conundrum in which a series of bad decisions degrades the trust in her own judgment. She’s developed the identity of an untrustworthy person to herself which leads her in a cycle of poor choices. It’s scenes like this that do justice to Baker’s brilliance as a playwright.

Though Janet Planet is her filmmaking debut, Baker is a celebrated darling of the theater world. Her cache of character-driven plays, known for their artificially deployed pauses, are punctuated by a Pulitzer Prize and MacArthur Fellowship. Though the stage is a much different medium than the screen, Baker successfully translates her dramatic tastes.

Much of the feature plays out from the perspective of a steadfast camera that lies still, watching the actors in their space much like looking at a stage. Even in close-ups, the lens acts as if it were sitting across from the character, patiently listening to what they have to say. The editing is slight, only cutting when the text requires it.

Baker makes superb choices with the elements that film offers and the stage simply can’t. Her locations all fit naturally in their 1991 setting, including the sun-bleached home that looks as if it would be a “Guest favorite” on AirBnb. The visuals of an outdoor play charm and intrigue you just as they do Lacy. Notably, Baker makes ingenious use of the obsolete edifice of our time: the mall. With so many in the country lying dormant, they provide an experience frozen in an era before the internet supplanted it. A sequence of Lacy and a friend making their way through the food court, fountains, and various shops feels so true to that time, it makes you miss the sterile consumerism of it all.

But Baker’s most impressive achievement is imported directly from her stage work –her characters. Janet Planet is a small, modest film. Its undeniable resonance comes from the empathy she’s able to establish with the viewer. Every time Janet brought a new man into her life, I squirmed in my seat, as I would in a horror film just before the character naively made a deadly turn. My most visceral connection was to Lacy, for whom I possessed a feeling of fraternal protection I’ve never felt for another character. If anything bad were to happen to her, I would have been unbelievably upset.

But nothing terrible happens. Baker doesn’t need to rely on any kind of dramatic crutch that would manipulate you into investing in Janet and Lacy. No one is sick. No one is dying. No one has any kind of high-stakes trauma they’re suffering through. There’s nothing pointing to whom you should be sympathetic towards. You just feel it in your heart, even as your eyes adjust to the world outside and you walk home.