Throughout his career, Martin Scorsese has shared his love for cinema with anyone who will listen. His celebrated work is included in any serious discussion of the American movie canon. His World Cinema Project restores the films of directors like Ousmane Sembène and Edward Yang. He lends his name and influence as a silent producer to a new generation of filmmakers including Joanna Hogg and The Safdie Brothers. Whether it’s at Q&As, on panels or on talk shows, he’s been a vocal public cheerleader for his artform.

With Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger, America's beloved motor-mouthed movie geek is here's to tell you all about the pair of British auteurs that influenced his work as well as that of his oft-mentioned contemporaries: Francis Ford Coppola and Brian DePalma.

In another instance of playing the film elder, Scorsese was one of the celebrity instructors in the subscription-based pop-academy, Masterclass. The video series presents the director in a comfortable chair, adorned with perfect three-point lighting as he directly addresses the camera with his insights on the craft of movie making. If that was Professor Scorsese's 101 level course, think of Made in Britain is his 201.

The documentary is Scrosese's own account of the work of Michael Powell and Emmerich Pressburger. Marty, and Marty alone, walks you through the directors’ oeuvre, blending biography with his own insights. Didactic as it is, it's also exactly what anyone who is interested in the title would want: a celebrated, contemporary master holds your hand on a tour of his underappreciated forebears. Film-by-film, he expounds on their mastery of the language of cinema, interpreting each film like a cinema studies seminar.

The story of The Archers, Powell and Pressburger’s production company, runs parallel to the history of Britain in the 20th century; their careers and work exist in direct conversation with the English World War II experience. At a time when the grit and cynicism of film noir was the popular genre of the day, Powell and Pressburger told elaborate stories with a lush, poetic vernacular.

British cinema was imbued with a sense of grandeur and imagination through films like

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Matter of Life and Death, and The Red Shoes. Powell and Pressburger films, while continuously ambitious, became increasingly daring as they indulged further into dreamlike imagery and unconventional form.

The beginning of any “Production of The Archers” was accompanied with a title card that reads “Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell and Emmerich Pressburger.” The imposing credit presents a bold declaration of auteurship, but there's some sour news for those under the impression the work was evenly split. An archival interview clip offers insight into their division of labor (Powell mostly directed, Pressburger mostly wrote the story, and they both produced). As powerful as the artistic statement is, the scale of their sky's-the-limit aspirations required collaborators who could do them justice.

Powell's early experience at Victorine Studios, making silent films for MGM, immersed him in the early world of large-scale filmmaking. To design the legendary staircase and heavenly world in A Matter of Life and Death, Powell and Pressburger conscripted art director Alfred Junge, who had worked at UFA studios, the home of Fritz Lang.

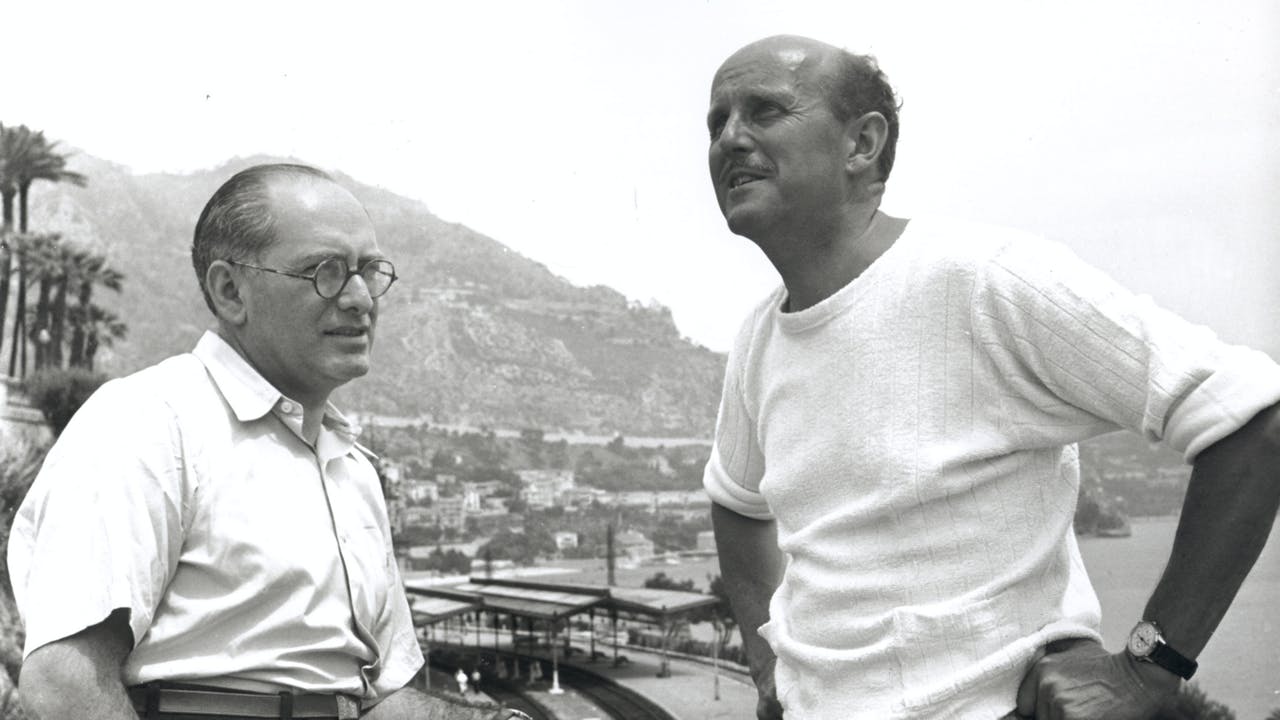

The focus skews more towards Powell as he and Scorsese shared a personal relationship. While making Mean Streets, Scorsese sought out Powell’s acquaintance as he was left to a quiet exile in the English countryside by the British film industry. The two struck up a relationship and Powell became his mentor, as well as the husband of his longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker.

Scorsese presents side-by-side comparisons of scenes and shots from Powell and Pressburger’s films alongside his own to demonstrate their immediate influence, but his appreciation extends beyond their artistry.

His reverence doesn't lie solely in the Technicolor movies that were instrumental to his love of cinema, but to kindred spirits within the filmmaking duo that shared in his uncompromising artistic vision. Not only did they show him how to make movies, they gave him a cautionary tale of how precarious that can be.

As Powell and Pressburger’s experimentation continued to grow, interest in their work waned. Their collaborations with Hollywood proved artistically stifling and unfruitful as the pair looked to less conventional sources to fund their goals. Michael Powell's brush with moving his work to TV feels like the unrealized version of Scorsese working with streamers.

“They wanted to hang on to their independence, and they suffered because of it,” Scorsese says almost autobiographically into the camera.

It's another example of the cyclical nature of filmmaking. The Movie Brats of Scorsese, DePalma, and Coppola rediscovered and elevated the work of Powell and Pressburger just as the French New Wave did with Alfred Hitchcock and Otto Preminger.

Culture seems to have a short memory for those we consider to be our legends. It takes effort to keep them in the conversation and remind us why they matter; and when we do remember it's difficult to think of how they could ever fall out of favor. The question that comes to my mind is not who will be the ones to remember the greats of our time, but how will they be forgotten?